Submarine Warfare and the First World War

Project Group: Würzburg University

Project Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Jacob

Project Participants: Riccardo Altieri, Philipp Amendt, Laura Metz, Florian Nolte, Tilman Sanhüter, Marc Schwenkert, Jakob Stahl, Philipp Vogler, Arne Weber

Project Participants: Riccardo Altieri, Philipp Amendt, Laura Metz, Florian Nolte, Tilman Sanhüter, Marc Schwenkert, Jakob Stahl, Philipp Vogler, Arne Weber

This is the song of the submarine

Afloat on the waters wide.

Like a sleeping whale

In the starlight pale,

Just flush with the swirling tide.

The salt sea ripples against her plates

The salt wind is her breath,

Like the spear of fate

She lies in wait,

And her name is Sudden Death.

I watch the swift destroyers come,

Like greyhounds lank and lean,

And their long hulks sleek

Play hide-and-seek

With me on the waters green.

I watch them with my single eye,

I see their funnels flame,

And I sing Ho! Ho!

As I sink below,

Ho! Ho! For a glorious game!

I roam the seas from Scapa Flow

O the Bight of Heligoland;

In the Dover Strait

I lie in wait

On the edge of Goodwins Sand.

I am here and there and everywhere,

Like the phantom of a dream,

And I sing Ho! Ho!

Through the winds that blow,

The song of the submarine! (1)

The submarine, described as a deadly and silent weapon in the above quoted poem, was one of the new aspects of the Great War. It was the use of modern technologies that changed the way wars were fought, especially with regard to the First World War, which made the interrelationship between warfare and technology itself obvious.(2) In this conflict, the armies that possessed the better weapons would be able to win decisive battles. The battles of materials became more important than personal skills or honor when the soldiers were forced to overcome the hardships of trench warfare on the Western front and many other battlefields of the Great War.(3) However, technology was not only used at land but also beneath the waves of the ocean. The submarine would become one of the decisive weapons of the conflict, which did not only fulfill the fantasy of Verne.(4) It seemed to be clear: the use of this new technology had changed the way of naval warfare.

The submarine and anti-submarine campaign is not a series of minor operations. Its history is not a mere episode among chapters of greater significance. On the contrary, the fate of Britain, and the fate of Germany, were speedily seen to be staked upon the issue of this particular contest, as they have been staked upon no other part of the world-wide struggle.(5)

The observations of those who recognized the changes of naval warfare went even further when they declared that the future of civilization depends on(6) the submarine. Again and again the successes of these new weapons had been underlined, especially by contemporary German publications.(7) It was also stated that:

Here (in the submarine warfare, F.J.) and nowhere else so clearly as here the world has seen the death struggle between the two spirits now contending for the future of mankind. Between the old chivalry, and the new savagery, there can be no more truce; one of the two must go under, and the barbarians knew it when they cried Weltmacht oder Niedergang.(8)

Consequently, the submarine did not only create a new possibility to threaten the enemy from beneath the sea, but it also created a new image of the war, one that was totally open for interpretation, ranging from a new ultimate weapon to the dishonorable way of warfare. The present evaluation of the role of the submarine during the First World War will, therefore, not only focus on the impact of the new weapon but also consider the new image of battle and honor that was produced by it.

Impact

The destroying impact of the submarine was mainly made possible by the combination of two technologies, namely the submarine itself and the torpedo as its deadly weapon.

While the term torpedo was used to describe a sea mine at the beginning of the 19th century(9), it would become a technology that allowed a speedy under water attack during

the Great War. The navy focused on the submarine and its potential for naval warfare for decades, especially since the turn of the century.(10) The first draft for a boat

that was able to function under the water went back until the late 16th century(11), but the first recorded experiment in submarine operation was made by a Hollander, Cornelius Van Drebbel,

who in 1624 constructed a one-man submarine operated by feathering oars, which made a successful underwater trip from Westminster to Greenwich on the Thames.(12) One of the

first military missions for a submarine occurred during the Revolutionary War in North America, when David Bushnell used the American Turtle, a one man submarine, to

almost sink a ship in the harbor of New York.(13) During the Civil War in the United States (1861-1865), one tried to intensify the military use of submarines, but failed.(14)

Despite the increasing technological options, the submarine remained a rather underdeveloped naval technology, and as late as 1904 the submarine was not considered by naval

authorities as a weapon of much value. (15)

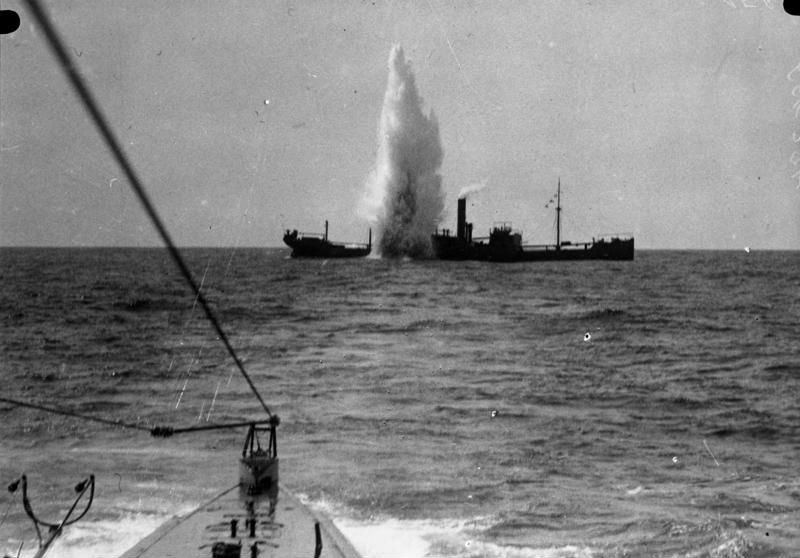

| British cargo ship SS Maplewood under attack by SM U 35 on 7 April 1917, 47 nautical miles/87 km southwest of Sardinia (Attribution: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00159 / CC-BY-SA) |  |

|---|

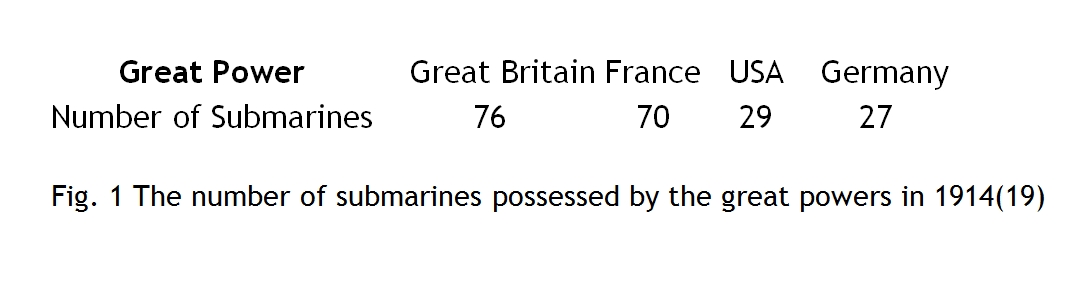

While the later Allied Powers seemed dominant at the beginning of the war, the German war planners would later recognize the importance of the submarine as a new technology

for naval warfare and try to establish a supremacy in numbers.(20) German advocates of the submarine warfare always claimed that there would be more potential with regard to

this new technology, which would provide the only option to defeat Germanys most dangerous enemy, namely Great Britain.(21)

Submarines would finally tip the scales that would be able to attack the Achilles heel of the British Empire.(22) It would be the victory against England that was needed to

win the war, and one should not care too much about the American criticism of the German submarine warfare because only a serious attempt to weaken the enemy could finally

provide victory. A reluctant position with regard to the unlimited submarine warfare would just strengthen the Allied Powers and weaken the German Empire.(23) As a consequence

, the weapon that was rather treated as unimportant before the First World War

[...] had made its presence felt as a most effective weapon. German submarines have translated into actuality the prophecies of Verne, and have altered the views not only of the English but of the world as to the efficacy of the submarine as a naval weapon.(24) Thereby and in this surprising manner that the submarine torpedo boat has emerged from its swaddling clothes and has begun to speak for itself. Its progress and development have been retarded for many years by the lack of appreciation of its possibilities on the part of those who have had the planning of naval programs.(25)

The naval staffs of all major navies now recognized the tremendous impact of the submarine, and it was concluded that as the motor has driven the horse from the road,

so the submarine has driven the battleship from the sea.(26) It was not only able to be used as a classical boat on the surface of the sea but also to function as an unseen

weapon from beneath the sea line, hitting its target like an assassin without being recognized before. Consequently, the submarine was also an expression of asymmetric warfare

(27) during the years of the First World War.

The war itself also provided a frame for an intensive phase of research and development with regard to the submarine technology:

The three years of conflict have, however, afforded an opportunity for a further and even more important comparison. The problems of submarine war are not all material problems; moral qualities are needed to secure the efficient working of machinery, the handling of the ships under conditions of danger and difficulty hitherto unknown in war , and the conduct of a campaign with new legal and moral aspects of its own.(28)

While the German navy tried to further increase the possibilities of the submarine, the Allied Powers were in search of suitable responses against the death from below the

sea. The German submarine rolled lazily in complete isolation, waiting, like a snake in the grass, for its prey,(29) while the British naval officers had to find an answer

to this invisible threat, which might just be targeted when the periscope was used by its commander to check the environment for possible targets.(30)

The British enemy readily admitted that they (the German submarines) have done well(31) and the image of the submarine commander as a silent hunter from below made the round

. Therefore, these submarine commanders were conventionalized as the new heroes of the naval battlefields:

The commander must possess the absolute confidence of his crew, for their lives are in his hands. In this small and carefully selected company, each man, from the commanding officer down to the sailor boy and down to the stoker, knows that each one is serving in his own appointed place, and they perform their duties serenely and efficiently.(32)

As the submarine war has proved to be the main battlefield of (the) spiritual crusade, as well as a vital military campaign,(33) the German submarine commander and his power to sink the glorious ships of the British fleet were delivering a new heroic image that was used for propaganda at the German home front as well:

| German propaganda Postcard / Ships sunk by the noted German raider U-9, commanded by Capt. Weddingen (George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress) |  |

|---|

As for the British, the day of their naval power was past; they had spent their time and money upon the mania for big ships, and neglected the more scientific vessel, the submarine, which had made the big ships obsolete in a single years campaign. The ship of the future, the U-boat, was the national weapon of Germany alone.(34)

It was the German submarine that became emblematic for this new way of naval fighting, while the French and British submarines were hardly ever mentioned in the news from the battlefield at sea. This situation tried to show that the Germans had no monopoly with regard to the use of the powerful new weapon, but they, nevertheless, fought the war in a dishonorable way:

The submarine is not, in its origin, of German invention; the idea of submarine war was not a German idea, nor have the Germans contributed anything of value to the long process of experiment and development by which the idea has been made to issue in practical under-water navigation. From beginning to end, the Germans have played their characteristic part. They have been behind their rivals in intelligence; they have relied on imitation of the work of others; on discoveries methodically borrowed and adapted; and when they have had to trust to their own abilities, they have never passed beyond mediocrity. They have shown originality in one direction only their ruthless disregard of law and humanity.(35)

Other writers tried to show the negative impact of the German tactics, whose planners will suffer the bitter consequences of moral outlawry.(36) Even though German authors later denied the cruelties by pointing to the fact that the commanders of the Imperial Navy of Germany had renounced broadening the unlimited submarine warfare(37), the sinking of unarmed ships used for commercial reasons made their position an accused one. While accused as a pirate, a German U-Boot Kapitän declared frankly:

As a seaman I regret having to sink any ship of commerce. As an officer of the German Navy I have to obey orders unquestionably. Nevertheless I have always given the crews of British ships a chance of escape, and have never sunk any vessel until the men are safely in the boats, unless she attempts to show fight or to run away.(38)

|

The track of Lusitania. View of casualties and survivors in the water and in lifeboats.(National Maritime Museum, Greenwich) |

|---|

However, the unlimited submarine warfare would finally lead to the participation of the United States in the war, a fact that is especially related to the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915(39), which proved to be only the black harbinger to a whole harpy-flight of German crimes in the South Irish waters.(40) The German navy had no other choice, as an open battle between the cruisers and heavy battleships seemed to be senseless. Just the new option of an asymmetric warfare beneath the sea line made a German success possible. That is why the navy staff finally decided to go on, knowing that this might create a larger scale of global warfare as a response. The sinking of numerous British ships in addition created a fierce anger against the German enemy since the sinking destroyed not only the material but also the pride of the natural seamen of England and the British Isles:

The sailor-boys would score jokes off one anothers petty misfortunes with all the light-heartedness which is said to mark the trench wit of the Doughboys and Tommies. Especially was this true of the professional seamen. Commend me to a sailor for a certain frank upstanding manliness which landsmen or certainly many city men seem to miss. The fact that the English are a seafaring people must surely account in no small measure for their retention of national stamina. The seas are Englands lungs, which renew and oxygenate her racial character.(41)

Consequently, the German strategy of naval warfare was condemned as being unethical and immoral:

The trampling upon diplomatic obligations and promises, new and old alike, which the Germans have made a part of their submarine campaign need only be barely mentioned; for the duplicity and scorn of honesty shown in Berlins negotiations regarding the undersea warfare are already a familiar reek in the nostrils of all intelligent men. The fact that the submarines never seek encounters with vessels of war, so that their operations have none of the redeeming heroic elements of combats between armed contestants, would doubtless carry no wormwood for men who are so devoid of sportsmanship to have coined the remark, You will always be fools and we will never be gentlemen ; but it will hardly appear devoid of significance to Americans.(42)

The attacks on non-military ships, the attacks on passengers, the civilian losses and the non-reaction to diplomatic pressure were finally responsible for the European war becoming a real World War, one that was also determined by the economic power of the United States. Finally, the Germans were seen to be heartless enemies that needed to be destroyed, as they had abused the modern technology to kill innocent people.

Neither d(id) the( Allied commanders) condemn the Germans for having caught up and used vigorously a horrible new weapon of warfare, such as the submarine is. All war is conducted with horrible weapons; and the submarine, if used against armed combatants, has hardly more intrinsic horror than the poison-gas which, because we have been forced to, we are now ourselves using.(43)

The Germans were condemned for using the weapons in an unjust way.(44) It was Germany, (who) in an excess of war fever, broke the sea laws, and laughed while women and

children drowned.(45) The Allied Powers, consequently, had to face a rough and merciless guerilla war at sea(46) and finally had to come up with a counter measure against

these barbaric tactics.

However, it was not easy to catch the enemy in this scenario, as anti-submarine warfare (was) very like big-game hunting. Success depends entirely on the initiative,

skill and resource of the individual hunter.(47) Furthermore, the German submarines, namely U-53, U-151, U-156, U-140, U-117, U-155, and U-152 also threatened the American

coast between July 1916 and October 1918. The submarine Deutschland(48) was even active before the war against the United States began, namely between July and August 1916.

It was finally the patrolling method(49) covering 180,000 square miles of the possible naval battlefield and the fact that the Germans did just possess submarine bases at the

shore of the North Sea that would decide the war. The danger zones could be limited to the North Sea and the English Channel, the Irish Sea as well as the Mediterranean and

the North Atlantic, a fact that combined with the patrolling system led to the destruction of more and more German boats. The British also started to secure their commercial

ships by sailing in convoys with large destroyers(50), while the attacks became riskier for the German commanders.

This led to a hunt for submarines, due to which the sailors might otherwise have had to wait more than half a year before the excitement of a real submarine hunt could take

over the entire crew.(51) Usually it were destroyers that were used for the hunt for the enemys submarines. Nevertheless, there were discussions about the use of the

underwater boats to create an underwater submarine war, which should here be quoted in detail:

The employment of submarines against submarines also forms a method of under-sea warfare which gives considerable scope for both daring and resource. It is of course quite impossible for one of these vessels when totally submerged to fight another in the same blind condition. But with just the small periscopic tubeor eye of the submarineprojecting above the surface, one craft can scout and watch for another to rise to the surface, thinking no enemy is near, in order to replenish her air supply for breathing or for recharging the electric storage batteries which supply the current for submerged propulsion. When such a position is obtained, the submarine which comes unknowingly to the surface stands a grave danger of being torpedoed by her opponent. This actually occurred to at least one German U-boat during the Great War. One or more submarines can also be employed around a slow-moving decoy ship. In this case they would have the advantage of being invisible until the actual moment of attack. The result of such a man[oe]uvre would be either a gun duel on the surface or the torpedoing of the attacking submarine by one or other vessel of the decoy's submerged escort.(52)

The submarine warfare had created its own dynamic by asking for economic support to build, equip and supply the new weapon during the war years. It was an essential new part of the naval warfare during the years 1914-1918 and would create several myths. One was related to the cruelties of the unlimited submarine warfare and the other one to the submarine commanders as the lone wolfs of the modern battle. Those men conquered a new sphere of fighting and were the last heroes of a modernized war because their talent was able to determine victory or defeat for the whole crew of a submarine. Therefore, the following part will highlight the experiences of the submarine crew-members and the captains during the new way of naval warfare during the First World War.

Experiences

Due to the increasing importance of the submarine as a new technology of warfare in the First World War, the image of the ocean itself also changed step by step.

The North Sea became a projection screen, with the hope of becoming rewarded as an honorary fighter, because especially in this new setting of war, the individual

impact on the outcome of a battle still seemed to be existent.(53) Those who became members of the crews of the German submarines were eager to pay their dues to

participate in this new heoric fight, one the Germans seemed to simply dominate at the beginnging as well. Later, authors remember their thrill of being personally

responsible for the sinking of so many of the enemys ships.(54)

The submarine crew members were often depicted as modern and honorary pirates(55). The men of the German Imperial Navy laid traps and hunted the enemys boats.

(56) While the Germans depicted the new way of warfare in rather positive ways, the British descriptions were tremendously different:

the British seaman has shown himself possessed, in the highest degree, of the qualities by which his forefathers conquered and kept our naval predominance; and finally, it is in the submarine war that we see most sharply the contrast of the spirit of chivalry with the spirit of savagery; of the law of humanity with the lawlessness of brute force; of the possible redemption of social life with its irretrievable degradation.(57)

The author goes even further by underlining the even more important role of the submarine warfare with regard to the cruelties that were becoming part of modern warfare in the Great War:

In the trenches, in the air, in the fleet, you will see the same steady skillful British courage almost universally exemplified. But in the submarine war, the discipline needed is even more absolute, the skill even more delicate, the ardour (sic!) even more continuous and self-forgetful; and all these demands are even more completely fulfilled.(58)

In addition to the new set of skills that were needed to fight this kind of war beneath the sea, the men had to get used to a new environment. While fighting on a ship was nothing uncommon for a British soldier who might have heard all the famous stories of the Battle of Trafalgar before, fighting beneath the sea, in a submarine, was something that rather remained to the world of legends and novels.

I must try and give some picture of the strange and unfamiliar world in which I found myself. Here I was sailing under the sea for all the world like someone in Jules Verne, experiencing something that only the tried men of the navies ever know. I was in a long, narrow tunnel, most brilliantly lit. The air was warm and close, tainted a little with a faint suggestion of chemical fumes. It was rather like being in a chemists shop in winter time when a large fire is burning.(59)

Many of the submariners were additionally fighting in an element they were not used to at all. Neither did they have too much knowledge about the ocean itself, nor were

many crewmembers able to swim. (60) One crewmember described that there was a tension both of physical atmosphere and mental excitement, strange and unnatural to me, but

which those who go beneath the waters and explore the mysterious deep always have with them.(61)

What was also clear to all participants of a submarine mission was that the crew acted as a unit, a community in which everyone would stand for another, because if one

made a mistake, the whole operation might have become a failure.

The same fate is shared by all, if the boat is destroyed and goes down the abyss. Heroes are in all ranks. And nobody knows if it will be the youngest seaman or the heater who will stand up in the highest danger to show that he is a guy with a reliable heart.(62)

A submarine, therefore, became the home for a community of fate,(63) and the commander was seen to be the soul of this community, the man who was responsible for the

life of all members. The group was also united by a whole setting of new experiences, often for the first time in their lives, that they shared with each other. When

the submarine went below the water line for the first time, the seamen were able to see the life under water through the available windows.(64) However, the reason for

their mission was to hunt the enemys ships and to attack them without any chance for the victim to escape the threat from below the sea.

While sending torpedoes into the direction of battleships, the crew was highly excited, and eagerness reached an almost endless level.(65) A successful hit against an

enemy made the submariners cheer even if the scenario above the water line after such a successful blow made the men aggrieved:

We in the tower tried to obliterate the impression of the debris field, with human bodies in the water, overturned boats, and leftovers of the ships to which drowning people were clipping themselves to, by assaulting the English, who had stolen Europe.(66)

After such a successful attack, the crew returned below the ocean where they took a rest until the next assault was due. During this time, the men were living a life in a cylinder(67), where half of the men were seasick half of the day, while the other men were cleaning the submarine.(68) Step by step, the men got used to the life under the sea, the hunt, and their new daily environment on board of a submarine:

The life on board becomes such a matter of habit that we can peacefully sleep at great depths under the sea, while the noise is distinctly heard of the propellers of the enemy's ships, hunting for us overhead; for water is an excellent sound conductor, and conveys from a long distance the approach of a steamer. We are often asked, How can you breathe under water? The health of our crew is the best proof that this is fully possible. We possessed as fellow passengers a dozen guinea pigs, the gift of a kindly and anxious friend, who had been told these little creatures were very sensitive to the ill effects of a vitiated atmosphere. They flourished in our midst and proved amusing companions.(69)

Caught British seamen described the German life even more accurate when they wrote about the German submarines in later days:

There were the living-quarters of the crew, kept spotlessly clean and tidy, yet Spartan-like in their simplicity. Two of the men were sound asleep in their bunks. Three more, who were playing cards at a plain deal table, glanced up from their game as the British lads passed by; but their interest was of brief duration, and stolidly they resumed their play.(70)

The men were segregated from the world above them for a long time. As a result, they used any opportunity to surface. On the deck in all conceivable attitudes were most of the U-boat's crew, taking advantage of a brief spell on the surface to breathe deeply of the ozone-laden atmosphere.(71) Besides those little pleasures, the crew was divided by hierarchy and some privileges were solely granted to the higher ranks:

Lieutenant-Commander Schwalbe, the Kapitan of U75. Schwalbe was sitting in a small arm-chair which had been brought from his cabin. He was smoking a cigar. At his elbow stood his satellite, Hermann Rix, who was also smoking. This luxury was denied (to) the crew, the officers being permitted to smoke only when the submarine was running awash or resting on the surface.(72)

What all crew-members were able to share were the side effects of serving on a submarine, a weapon that was definitely modern for its time, but also not perfect yet with regard to the human factor that had to live inside it.

Notwithstanding certain assertions in the press of alleged discoveries to supply new sources of air, the actual amount remains unchanged from the moment of submersion, and there is no possibility, either through ventilators or any other device so far known in U-boat construction, to draw in fresh air under water; this air, however, can be purified from the carbonic acid gas exhalations by releasing the necessary proportion of oxygen. If the carbonic acid gas increases in excess proportion then it produces well -known symptoms, in a different degree, in different individuals, such as extreme fatigue and violent headaches.(73)

Considering all these aspects, the seamen had a life of routine undersea that was impacted by different aspects of discomfort, e.g. the claustrophobic environment to name just one at this point. The commander was the only link to the outside world, deciding about what and in which direction it would happen.(74) In later descriptions, many authors tried to link the life on a submarine to ideals of manhood and bravery(75), and German authors tried to defend the methods of the unrestricted submarine warfare by pointing to the chivalrous habits of the German submarine commanders and seamen.(76) Many of the men serving on submarines did not believe in such images though because they recognized the truth that there cant be honor in attacking someone unnoticed. Therefore, the naval warfare of the First World War was as technologically driven as the war on land. For the seamen, survival was the consequence of a functioning collective on the boat while clear hierarchies and rules were determining their days. The men also knew that if they would be caught, their life would end anonymously and without any songs in their favor, exactly there where most of its recent part had taken place before: under the sea.

References

(1) William Booth, The Song of the Submarine, Truth, 4 November 1914.

(2) The First World War is usually depicted as the first really industrialized war.

(3) The impact of the use of modern technologies, like artillery and the machine gun were also visible on the periphery of the First World War, e.g. during the Gallipoli campaign. On this theater of war see Robin Prior, Gallipoli: The End of the Myth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

(4) Simon Lake, The Submarine in War and Peace: Its Development and its Possibilities (Philadelphia/London: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1918), 1.

(5) Henry Newbolt, Submarine and Anti-Submarine (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1918), 4.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Hermann Bauer, Das Unterseeboot: Seine Bedeutung als Teil einer Flotte, seine Stellung im Völkerrecht, seine Kriegsverwendung, seine Zukunft (Berlin: Mittler&Sohn, 1931), 5.

(8) Newbolt, Submarine, 7-8.

(9) Robert Fulton, Torpedo War and Submarine Explosions (New York: William Elliot, 1810; Reprint: New York: William Abbatt, 1914), 7.

(10) Naval Consulting Board and War Committee of Technical Societies, The Enemy Submarine, Bulletin No. 2 (New York: Naval Consulting Board of the Unites States, 1918), 6.

(11) Wiliam Monson, Inventions or Devises (London: 1578).

(12) Naval Consulting Board, Enemy Submarine, 9.

(13) Ibid.

(14) Ibid., 10.

(15) Lake, Submarine in War, 2.

(16) Small submarines were available but were almost not used during the Russo-Japanese War.

(17) Whitehead was one of the major developers of torpedoes.

(18) Henry Newbolt, A Note on the History of Submarine War (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1918), 19.

(19) Ibid., 20.

(20) For a fast access list of most of the German submarines that were part of the Imperial German Navy see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Submarines_of_the_Imperial_German_Navy (Last access, 8 March 2015).

(21) Walther Vogel, Die entscheidende Bedeutung des Unterseebot-Krieges (Berlin: Saling, 1916), 1.

(22) Ibid., 1-2.

(23) Ibid. 4.

(24) Lake, Submarine in War, 2.

(25) Ibid., 3.

(26) Ibid., 4.

(27) For a survey of the concept of asymmetric warfare see William C. Banks, New Battlefields - Old Laws: Critical Debates on Asymmetric Warfare (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).

(28) Newbolt, Note, 21.

(29) Georg-Günther von Forstner, The Journal of Submarine Commander von Forstner (Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917), 15.

(30) Ibid.

(31) Newbolt, Note, 22.

(32) Forstner, Journal, 15.

(33) Wesley Frost, German Submarine Warfare: A Study of ist Methods and Spirit (New York/London: D. Appleton and Company, 1918), 7.

(34) Ibid., 10.

(35) Ibid., 11.

(36) Newbolt, Note, 22.

(37) Bauer, Unterseeboot, 78.

(38) Percy F. Westerman, The Submarine Hunters: A Story of the Naval Patrol Work in the Great War (London et al.: Blackie and Son, 1918),

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/26641/26641-h/26641-h.htm#chap05 (Last access, 8 March 2015).

(39) On the Lusitania see the recently published volume Erik Larson, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania (London: Doubleday, 2015).

(40) Frost, German Submarine Warfare, 3.

(41) Ibid., 12.

(42) Ibid., 138-139.

(43) Ibid., 141.

(44) On the concept of just war see Michael Farrell, Modern Just War Theory: A Guide to Research (Lanham et al.: Scarecrow Press, 2013).

(45) Charles W. Domville-Fife, Submarine Warfare of To-Day (London: Seeley, Service & Co., 1920), 9.

(46) Ibid., 11.

(47) Ibid., 126.

(48) The submarine Deutschland was also becoming a symbol of German submarine warfare, simply due to its name.

(49) Domville-Fife, Submarine Warfare, 131-134.

(50) Ibid., 131.

(51) George M. Battey, Jr., 70,000 Miles on a Submarine Desroyer or: The Reid Boat in the World War (Atlanta: The Webb & Vary Company, 1919), 106.

(52) Domville-Fife, Submarine Warfare, 140.

(53) Albert Gayer, Die deutschen U-Boote in ihrer Kriegsführung 1914-1918, 2. Heft: Die U-Bootsblockade Februar bis Oktober 1915 (Berlin: Mittler, 1920), 27.

(54) Max Valentiner, 300 000 Tonnen versenkt! Meine U-Boots-Fahrten (Berlin: Ullstein, 1917), Preface.

(55) Max Valentiner, Der Schrecken der Meere. Meine U-Boot-Abenteuer (Leipzig: Amalthea, 1931), 72-79.

(56) Ibid., 72.

(57) Newbolt, Submarine, 4-5.

(58) Ibid., 7.

(59) Guy Thorne, The Secret Service Submarine: A Story of the Present War (New York: Sully & Kleinteich, 1915), 147.

(60) Max Valentiner, U38: Wikingerfahrten eines deutschen U-Bootes (Berlin: Ullstein, 1934), 49.

(61) Thorne, Secret Service Submarine, 148.

(62) Karl Dönitz, Die U-Bootswaffe (Berlin: Mittler, 1939), 27.

(63) Ibid.

(64) Johannes Spiess, Wir jagten Panzerkreuzer: Kriegsabenteuer eines U-Boot-Offiziers (Berlin: E. Steiniger, 1938), 11-12.

(65) Ibid., 32.

(66) Ibid., 36.

(67) Forstner, Journal, 16.

(68) Martin Niemöller, Vom U-Boot zur Kanzel (Berlin: M. Warneck, 1934), 13.

(69) Forstner, Journal, 6-7.

(70) Westerman, Submarine Hunters, chapter V.

(71) Ibid.

(72) Ibid.

(73) Forstner, Journal, 8-9.

(74) Ibid., 14.

(75) Julius Küster, Das U-Boot als Kriegs- und Handelsschiff: Die technische Entwicklung und Anwendung der Tauchboote, deren Motoren, Bewaffnung und Abwehr (Berlin: Klasing, 31917), 154-155; Hans Rose, Auftauchen! Kriegsfahrten von U53 (Essen: Essener Verlagsanstalt, 81943), 8-9.

(76) Reinhard Scheer, Vom Segelschiff zum U-Boot (Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1925), 321.

Impressum-Uni-Stuttgart ; data privacy statement of Uni Stuttgart